Each para should be capable of being read as a stand-alone. (These para will eventually go into a larger meandering-to-learn system. In most cases, the Entry should be one para—mini movement lessons are the exception.) I’ll be adding in videos and animations… and anatomy drawings. These aren’t in any particular order—you should be able to pop around however you wish.

Here are the written entries so far:

All Entries

updated July 28

Muscles, Fascia, Systems

'Voluntary' is a delusion

It's not Just the Neurons!

20th c Distinction between Voluntary and Autonomous Internal Adjustments

The Most Obscure Interoceptive Systems

Translucence in the 'middle muddle'

Awareness arising from movement

Organismic

The Stories Science Tells

Definition of Interoception

It isn't just the nervous system

Not-Fixing

Fixing is a heavy box

Moshe's nervous system in historial context

Organismic Networks

Interoception

What is Pain

Fascia and Fluids

The First Rib

Imagine you have One Shoulder Join

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Muscles

Proprioception 4 tired old notions

Seven Diaphragms and Pressure Gradient

Pain: Interoceptive Information Synthesis

Nociception as Threat Detection

Pain and Fascia

The Bottom Not-layer

Awakening the Opaque-ish Parts

Who is in Charge of Transformation

When Bone Density Challenged Clue’s Framework

Sore After Lesson?

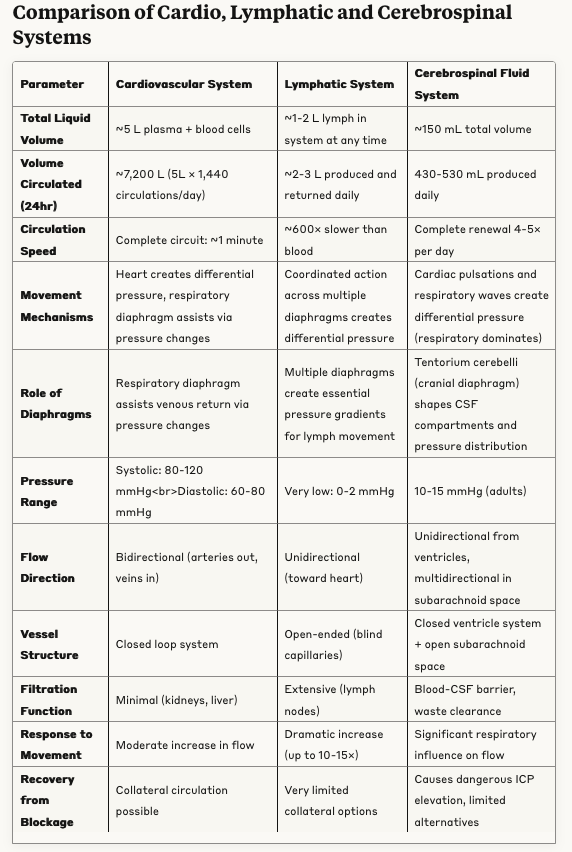

Comparison of blood/heart with lymph/fascia

Cardio/Facial/Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation

Redo of skeletal

Redo of Diaphragm

Seven Diaphragms and Pressure Gradients

Finding a Fascial Pattern, but not necessarily 'consciously'

Finding a Pattern using your imagination

Finding a Habit: The Nanosecond of Almost-Engagement

Finding a Chronic Contraction: Inside and Outside (mini lesson)

Finding a Fascial Pattern and sending it on vacation (mini lesson)

Why I Usually Don’t Demonstrate

The Real Reason I Usually Don’t Demonstrate

Nostril Dominance

Glymphatic System

Craniosacral Fluid

Why Does Fluid Circulation in the Brain Matter for Body Wisdom?

Muscles, Fascia, Systems

Thinking about muscles draws our mind to a reductionist approach. Reduction breaks something magical into component parts until the magic disappears, then studies the pieces. Muscles lend themselves to that kind of separation: the biceps, triceps, quadriceps [anatomical drawing]. They fit with linear analysis, cause-and-effect thinking, strain, willpower, and injury. If you want to think in systems--messy, complex, collaborative, communicative, integrative--then fascia becomes your framework. The fascia is the connective tissue that helped old anatomists see separate muscles, then got thrown away before the anatomist started drawing. So they literally threw away the connective tissue.

'Voluntary' is a delusion

The illusion of conscious will emerges from temporal misattribution between neural commitment and subjective awareness of intention. Libet's seminal experiments demonstrated that the readiness potential—measurable neural activity indicating motor preparation—begins approximately 550 milliseconds before participants report conscious awareness of their intention to move. Subsequent neuroimaging studies using fMRI and EEG have extended this temporal gap, showing that specific motor decisions can be decoded from neural activity in the frontopolar cortex and parietal cortex up to 7-10 seconds before conscious awareness of choice. The supplementary motor area and pre-supplementary motor area exhibit preparatory activity that precedes subjective intention by several hundred milliseconds even for seemingly spontaneous movements. This temporal architecture suggests that what we experience as conscious decision-making represents post-hoc narrative construction by prefrontal and anterior cingulate regions rather than causal initiation of action. The sense of agency—the feeling that "I" caused this movement—appears to be a retrospective attribution mechanism that creates coherent selfhood from the distributed processing of motor planning, sensory prediction, and outcome monitoring systems. Even complex cognitive decisions show neural commitment patterns that precede conscious deliberation, indicating that the experience of voluntary choice may reflect the brain's continuous predictive modeling and action selection processes rather than a discrete moment of conscious will. The conscious mind functions more as an interpreter of decisions already made by unconscious neural networks than as the executive controller it subjectively appears to be. (And a lot of Feldenkrais is about sneaking past that delusion and addressing the real influencers of movement.)

It's not Just the Neurons, Stupid!

The 20th century obsession with neurons as the primary communication network obscured a far more complex reality: your body processes information through multiple integrated systems working in concert. Moshé Feldenkrais talked a lot about the ‘nervous system’, which made sense in a historic context, but he kind of missed the boat. While neuroscience dominated the conversation about sensing and responding, the vascular system carries chemical messengers, your lymphatic network transports immune signals, your endocrine glands release hormonal cascades that travel through tissue and fluid and your immune cells function as roving memory keepers, storing information about past encounters and current threats. These systems don't operate in isolation or report to the brain like dutiful servants. Instead, they engage in constant cross-talk: immune cells influence hormone production, vascular changes affect neural signaling and hormonal shifts modify immune responses. Your gut produces more neurotransmitters than your brain. Your heart has its own neural network capable of learning and memory. All of this involves prodigious cross-talk, difficult allocation of resources, and real-time coordination challenges that are probably better understood as complex adaptive systems than command-and-control structures. If you sense something interoceptively—an emotion, a tendency, an appetite —multiple information systems are synthesizing data including chemical gradients, pressure changes, immune surveillance, and tissue tension—creating a form of distributed intelligence that makes purely neural explanations seem quaint and reductionist.

20th c Distinction between Voluntary and Autonomous Internal Adjustments

In 20th century thinking, 'voluntary' bodily actions were defined as willed and conscious--actions like raising your arm--while 'autonomous' systems were inaccessible, automatic, out of our control. This voluntary/autonomous distinction backed up the Rationalist idea of the brain as Big Boss. But it turns out that both of them are nonsense. I went into the research because my hunch is that a lot of things considered to be ‘autonomous’ aka ‘unconscious’ or ‘automatic’ or ‘unthinking’ and certainly uninfluenceable really are influenceable. That almost everything, from bone density to temperature regulation to pain to which nostril dominates at a certain time—fall somewhere on the ‘translucence’ spectrum and almost all of them are influenceable and most importantly that the practice of Feldenkrais gets at influenceable in ways that even Moshé Feldenkrais didn’t foresee. And I found plenty of evidence for that! But what I also found, to my surprise, is that the ‘voluntary’ category is as much BS as the ‘autonomous’ category. It isn’t accurate to think of the conscious brain making a decision and sending the command down to be executed, a command like ‘reach for the cup.’ In actuality, your organism will already have decided on, recruited and begun the movement. Then the consciousness—the ego—says ‘oh look at powerful me, I’m going to decide to reach for a cup.’ The consciousness is like a person who comes to a surprise birthday party and then congratulates themselves for what a great idea that was and how well prepared they were. What 20th c folks saw as ‘voluntary’—controllable, conscious—is in truth an after-thought.

Interoception can be Accessible [this is the geekier version of ‘20th c distinction… I think]

Contemporary neuroscience reveals interoceptive systems as existing along a continuum of neural accessibility and conscious modulation rather than discrete categories. This spectrum encompasses systems with minimal conscious access—such as osteoblast/osteoclast activity in bone remodeling governed by mechanotransduction pathways and hormonal cascades—to moderately accessible homeostatic circuits like thermoregulation, where advanced practitioners can influence hypothalamic-peripheral feedback loops through techniques that modulate sympathetic/parasympathetic balance. Motor control systems demonstrate conscious intention interacting with unconscious postural adjustments, cerebellar predictive modeling, and spinal pattern generators, revealing supposed 'voluntary' movement as emergent from distributed neural networks rather than top-down executive control. Complex regulatory systems including circadian timing mechanisms and emotional processing can become accessible through contemplative practices that enhance interoceptive sensitivity and modify cortico-limbic connectivity patterns. Rather than representing truly autonomous versus voluntary domains, these systems reflect varying degrees of neural plasticity, interoceptive resolution, and the capacity for conscious-unconscious integration within distributed processing networks. The binary framework obscures the reality that conscious access and regulatory influence exist as dimensional properties shaped by developmental history, attentional training, and the inherent architecture of specific neural circuits.

The Most Obscure Interoceptive Systems

Your tracking of internal systems is a bit of a sandwich. The ‘top layer’ is consciousness, and we believe we are conscious of, say, how we move our arm. There is a middle area of glimpses of awareness. At the bottom ‘layer’ lie the most obscure bundles of data collection, analysis and direction. They are usually opaque to us: a (mostly) wordless system of sensation and intelligence that has frankly probably gotten rather bored with you. Each time you are hurt or at risk, it has faithfully loaded on another set of protections. Over time, it may respond by habit, the great stultifier. This aspect of yourself is capable of learning, but it might have sort of forgotten how. And because of this slow narrowing of its attention, it has come to resemble what scientists of the 20th century called 'autonomous.' The bottom layer, which is capable of so much, fell into the story of the little homunculus mechanically and soullessly ticking away at its little preordained job. And that story is neither true, nor useful, nor necessary. It is a story of inaccessible habit.

Translucence in the 'middle muddle'

You could think of the 'bottom layer' of your inner perceptions--the almost-inaccessible part of your noticing--as a gray zone because it is opaque but not completely lost to your awareness and influence. The 'middle muddle' of your intelligence is the part of you that has taken material from that bottom layer and brought it into translucence. This layer isn't transparent, but it is accessible. Sometimes you can only catch a glimpse of it out of the corner of your eye. Sometimes it almost communicates with you in words. Sometimes it is a gut feeling or sense of a plumb line leaning you in a certain way, dropping an interoceptive hint. Or maybe you see it in colors or like a tuning fork. When you access this middle muddle, you have an increased potential for learning, for refinement. And this shift to learning in one domain--say, learning more about how you reach for a cup--seems to enliven much of the bored old bottom layer, not just the part that is responsible for how you move your arm. You remind the middle muddle that it is a learning system and that learning can be a lot of fun. Slowly but surely other formerly-opaque parts of the bottom layer become more alive, more curious, better at communicating with all the systems that are you. They make appearances in the middle muddle.

Awareness arising from movement

In a recent interview, Mia Segal, an early collaborator in the development of the FDK method, referred to 'awareness through movement' as brilliant nomenclature. I thought 'holy @#!, NO it is such meaningless jargon.' But I was wrong. It took me a long while to get that Moshé and Mia named it 'awareness through movement' not 'movement through awareness.' Or as another great teacher, Marilupe Campero said in a lesson 'don't pay attention in such a way that you can move better, move in such a way that you can pay attention better.' Sure, Moshé was interested in his clients' knee or hip pain or freedom of movement in the shoulder girdle. But he was a lot more interested in their mind--in their awareness. And if the awareness is a way to get to the hip joint organization, it isn't so much because the big, bossy, late-to-the-party consciousness has focused better, but rather because the student has relaxed into a zone of mental plasticity, the middle muddle, where almost anything is possible.

Organismic

"Organismic" is a term our AI coined because we couldn't find a satisfying word that avoids outdated body-mind splits. When we say "organismic intelligence," we mean the integrated coordination of all your communication pathways working together as a whole. It's not your brain controlling your body or your body influencing your mind - it's your entire organism functioning as a collaborative network where intelligence emerges from the interactions rather than residing in any single location. This organismic perspective recognizes that sensing happens in the perpetual negotiations among your multiple systems. It is in that ongoing dialog, using your distributed intelligence, that healing, learning and adaptation might happen. So it is no wonder that you might descend into this muddle of complex sensations about your sore hip, and emerge with a more elegant organization not just for your hip movement but for some seemingly unrelated part. (Such as how you talk with your neighbor about the barking dog.)

The Stories Science Tells

Science often echoes cultural stories rather than objective observation. When dominant culture was enamored with brain-in-a-jar thinking, science overemphasized the blood-brain barrier. During the Cold War, the "Naked Ape" story dominated over the collaborative, sexy bonobo as our progenitor. The "5 senses" framework ignores vibration, interoception, proprioception, and most of the sensing we actually use. The distinction between "voluntary" and "autonomous" systems supports cultural myths about willpower and control rather than reflecting how bodies actually work. These aren't minor oversights - they're examples of science serving cultural narratives instead of describing reality. The stories shape research priorities, funding, and what gets taught as fact. When the cultural investment is deep enough, contradictory evidence gets ignored or dismissed rather than integrated.

Definition of Interoception

Interoception refers to the processes by which your organism senses, interprets, integrates, and regulates signals originating from within itself. (NIH)

It isn't just the nervous system

We're witnessing a revolutionary shift from nervous system supremacy to distributed intelligence - fascia as information highway, gut as neurotransmitter factory, immune cells as memory keepers. The systems involved in processing signals about your internal environment include not only the peripheral nervous system and central nervous system, but also components of the vascular, endocrine, and immune systems.

Not-Fixing

One thing that distinguishes Feldenkrais from other modalities is its principle of not-fixing. However much trouble they (we) may have with sticking to this, it is a core principle and it matters. To fix is to have an ambition, and ambition, paradoxically, can get in the way of real healing. And to fix is also, of course, a profound arrogance.

I have been a mediator for 30 years, and the first time I held one of my fellow students' in the palms of my hands, I thought, as though with trumpets in the background 'ahhh, this is like all the best parts of mediation but without the bullshit.' As a mediator, my lodestone, my bedrock, my survival, my inspiration was to NOT FIX the parties. To not solve the problem. Just to create the space within which the parties could solve their own problems, within themselves and among themselves. And that is the paradox of Body Wisdom or the best of Feldenkrais: we are creating the space for you to teach yourself. You have the answers inside yourself. Your own teacher knows one billion times more about what you need than I do. And, perhaps most importantly, it knows/you know the when of your healing and even the how of your healing. Perhaps my best role is to flirt a bit with your inner teacher.

Fixing is a heavy box

When you are lifting a box, that is not the time to reorganize how you use your spine. Put the box down. Lie on your back. Bend your knees, if that is more comfortable. Sink into the floor. Breathe. Shift to your parasympathetic system. Now you can be aware of how you organize your spine. (And then in sitting, and in standing, and in walking… but first flat on the floor w/o the @#! box.) Having the intention of fixing something is another form of carrying the box. It is an imposition of will. It is a weight. It is very much from the 'conscious,' analytic, striving part of you. I'm not against those parts of you--or of me--but I think it is a good general rule that almost everything within us should be capable of taking a break some time. Body Wisdom is a time to take a break from carrying that heavy box of 'ought.' And then just feel… just explore… just give your brain a chance to play in this immensely spacious panoply of possibilities. Therein lies the magic.

Moshe's nervous system in historial context

Moshé Feldenkrais didn't have--science didn't yet offer him--the vocabulary that would allow him to get past the brainy-mind and to the whole-self mind. He talked about the 'nervous system' where we might better refer to organismic systems interacting in a non-hierarchical way. He was still stuck, sometimes, in the brain-in-a-jar themes of the previous centuries. But he still knew, in his bones, what he needed to know. He still knew that somewhere in the organismic middle muddle, healing could happen. He knew that if you move slowly and gently and lovingly enough, an awareness would blossom, and that awareness would extend to more than your knee or hip or shoulder girdle. He knew how to get consciousness and body sensations to dance together.

Organismic Networks

Your body processes signals through multiple pathways: neural networks, vascular systems, lymphatic channels, endocrine glands, and, especially, fascial networks. Information flows in from your external environment through vision, hearing, touch, taste, vibration and smell, while signals from your internal landscape carry news about heart rate, breathing, digestion, tension, timing and tissue health and many other categories. These systems don't operate independently - they're constantly weaving in a multi-dimensional loom, creating integrated responses that involve your entire organism. Your response include neural activation, hormonal cascades, immune changes, fascial tension and altered sensing—all happening simultaneously. The communication flows in multiple directions - not just the brain sending orders downward, but organs updating each other, tissues coordinating with distant body parts, and major pathways like the vagus nerve creating direct gut-brain conversations faster than conscious awareness can track or the conscious gray matter can keep up with.

Interoception

Interoception refers to the processes by which your organism senses, interprets, integrates, and regulates signals originating from within itself. Think of it as your body's internal communication network - fascia, heart, lungs, stomach, muscles, and other systems constantly sharing information and coordinating responses throughout your entire organism. This includes both ascending and descending pathways, creating continuous multi-directional conversations between all your systems rather than one part controlling the others—it is not just top-down. The impact of interoception extends beyond basic maintenance - it's fundamental to motivation, emotion, social awareness, your sense of self and knowing where you are in space or time. When you feel your heartbeat during excitement, notice your breathing becoming shallow with anxiety, or sense that pre-hunger stomach emptiness, you're experiencing interoception. Pulling interoceptive signals into awareness is a key to Feldenkrais.

What is Pain

Oh, pain is fascinating and confusing and kind of messed up! Fascinating because it busts through past the opaque almost-oblivion part of your sensations, through the middle muddle where you can usually only get glimpses of awareness and straight into your consciousness—like a sharp knife through butter. Pain is confusing because it isn't a particular signal that sends 'pain' messages. It is an emergent property of many sensorial streams—pressure, shear, temperature, chemical irritation, tissue stretch and myriad others. A key input is nociception. This was often thought of as the pain sensor, but it isn’t exactly. It is the signal for when you are threshold-busting. But the conclusion 'ouch' mixes all the signals from your nevrous system, lymphatic system, etc etc but it is ALSO composed of attitudes, beliefs and your understanding of your context inside and out. 'Belief' could be belief in healing or fear that someone powerful stuck a pin in an effigy of you. Belief that you are not worthy or your gender is stronger. Belief that you are too old… Assessment of your current stress context inside and out. All these contribute to the emergent property of ‘ouch.’ And, finally, pain is messed up because it doesn't undo its signal as easily as it registers/creates it. It is as though once pain emerges, once your consciousness grabs it, it isn't so good at ungrabbing it, even after the crisis is passed. Your consciousness gets its fingers stuck in the pain jar, and the harder you try to pull them out, the more the jar comes with you. And that is how the story of pain as an emergent property becomes the story of habits gone stale. Feldenkrais can do something about that.

Fascia and Fluids

The fascial system is like your body's internet - a communication network that connects everything. (Really. Everything.) [But somehow this paragraph stopped being about communication networks and became about fluids…. Need a para about speed of communication in fascia, neuroreceptors, embryology…]

It's woven together with your blood vessels, the tubes that drain swelling, and your immune system. When fascia gets tight and stuck, it's not just movement that suffers. The fluid highways throughout your body get squeezed too. Think of it like stepping on a garden hose - everything downstream [and upstream?] gets affected. Your lymph system (which cleans up cellular trash and fights infection) relies on fascia to help pump fluid around. When fascia can't move freely, waste builds up and inflammation spreads to places that seem totally unrelated. A tight area around your first rib doesn't just affect your neck and arms - it can mess up drainage throughout your whole upper body. Medical school teaches these systems as separate subjects, but your body built them as one integrated network.

The First Rib

The first rib creates the only fixed place for the entire shoulder girdle system and oooh is it fixed! The shoulder blades float and the clavicles hang. In tensegrity terms, the parts of your shoulder joints don’t so much make a ‘locked kiss’—the way, say, the ball and socked of your hip does—as a butterf[y touch. The shoulder joint parts just touch up against each other, never nailed down. It is only the first rib that forms a complete anchor at both ends - in the back to the top thoracic vertebra (that big knob at the base of your neck) and in the front to the sternum at the thoracic inlet. All the other ribs have moveable joints in the back. But not the first rib. This attachment of the first-rib-necklace creates a stiff foundation that everything must organize around. When the first rib becomes restricted or elevated, the entire floating apparatus of shoulders, arms, and neck has to compensate. This has a profound effect on the at least two diaphragms— the breathing diaphragm at your lower ribs and the diaphragm near the notch of your collarbone.. The scalenes attach directly to this necklace, so if they have chronic tension, it literally pulls the shoulder girdle upward, messing with the breath and the neck and the head and the thoracic outlet and the pressure on the vagus nerve and your self-management of the pressure gradient from the little hammocky diaphragm at the base of your brain all the way down to your anus… and the everything. Your thymus. They are all implicated. And when the first rib comes unstuck, it feels so good.

Imagine you have One Shoulder Joint

Notice how you are sitting or standing now. Don’t fix it. Notice the movement of your breathing diaphragm. (You can curl your fingers up under the floating rib if you need to identify that muscle—which is not a very easy muscle to feel directly. Tuck your fingers there and laugh or cough… yup. There it is.) Don’t fix it, but do notice if you spontaneously find yourself taking a deep, satisfying breath at some point. Notice your shoulder joints. Wiggle them around a bit: Clavicles (collar bones), shoulder blades, humorous (top long bone of the arm). Put the tips of your fingers on your clavicles and notice how they move—very little, probably, but that little bit is so important. Feel at the back for the knobbiest knob at the base of your neck. And then the notch in front where your clavicles attach-ish to the top of your sternum. If you can imagine the necklace of the 1st rib, tucking into the notch and attached to the knob… Admire this costovertebral joint as perhaps the most complex part of the entire skeleton. (Only the ankle is as cool as the costovertebral joint IMO.) Wiggle around, change your weight on your feet or your seat. Follow your first rib in your imagination or else pretend that you can.

And now… let that go… and let go of the idea that you have two shoulder joints. Take the idea that you have just one: at the center, in front, at the costovertebral joint. And now wiggle! Wiggle as though you grew up all your life just thinking of having that one joint and all the rest of the shoulder apparatus is just a loose, even pleasantly ramshackle, floating bit of tensegrity, a constant harmony between friendly force, suspended from the notch in front and the knob in the back of your three-dimensional self. Find a movement of your arm that interests you and go back and forth between the ‘one joint’ imagination and the ‘two shoulder joints’ imagination? Does this subtly play with the way you organize yourself? Your elegance? Your mood? (Or not?) How does your breath respond?

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Muscles

Focusing on a single muscle leans you away from thinking about the whole body. And there's a bigger problem: there's a strong likelihood of focusing on the wrong muscle. The one that hurts may be compensating for something more interesting. It is often the big brawny extrinsic muscles take the limelight when the more interesting support might come from the small, delicate, mysterious intrinsic muscles. The intrinsic muscles, like the fascia, develop very early in the embryo. They are the ones that work within a particular system—in the hand, along the spine, inside the eye—, whereas the extrinsic muscles are the big levered ones that connect different parts—the neck and the first rib, the chest and the arm, the torso and the leg, the hand and the lower arm—in order to lift, bend, hold up or do other Big Work that gets lots of attention. In a Body Wisdom movement class, part of the magic depends on accessing the intrinsic muscles while inviting the extrinsic ones to melt into the background for a little while. It is the intrinsic muscles that have the basic blueprint, that are best at reorganizing, that are smarter at finding easier options. If the extrinsic muscles can just give the intrinsic muscles 'a moment,' the intrinsic muscles can actually provide better support for the whole system.

Proprioception 4 tired old notions

Proprioception is a term in flux. It could mean any kind of interoception that helps us know where we are in space. But it turns out that the majority of our interoceptive systems are at least partially dedicated to figuring out where we are in space, so that's not a useful distinction. A second 20th c notion about proprioception was the wonderfully circular 'that which takes information from proprioceptors.' That's kind of useful if you know that proprioceptors measure the stress of gravity and other pressures.

(One way to know where your hand is in space, when your eyes are closed, is to feel the weight of your arm. Try it! Close your eyes, extend your arm, feel the weight. Now bend your elbow and bring your hand close to your chest. Which position would you choose if you knew you had to hold it for 10 minutes? That's your proprioceptors talking.)

A third bit of 20th c thinking was that proprioception takes place in the muscles, tendons and ligaments. True, but so much more proprioceptive signaling—more than those three combined—takes place in the fascia.

And the last debunked idea is that the nervous system sits on top of all this, gathers all the information, and then exerts its command and control. Nope. that's not correct. The fascia, in a tremendously complicated collaborative dance, in combination with neural, immune, and other loops, is probably the lead. But mostly, no single actor really leads—it is a chorus. Knowing where you are in space turns out to be a chorus without a conductor.

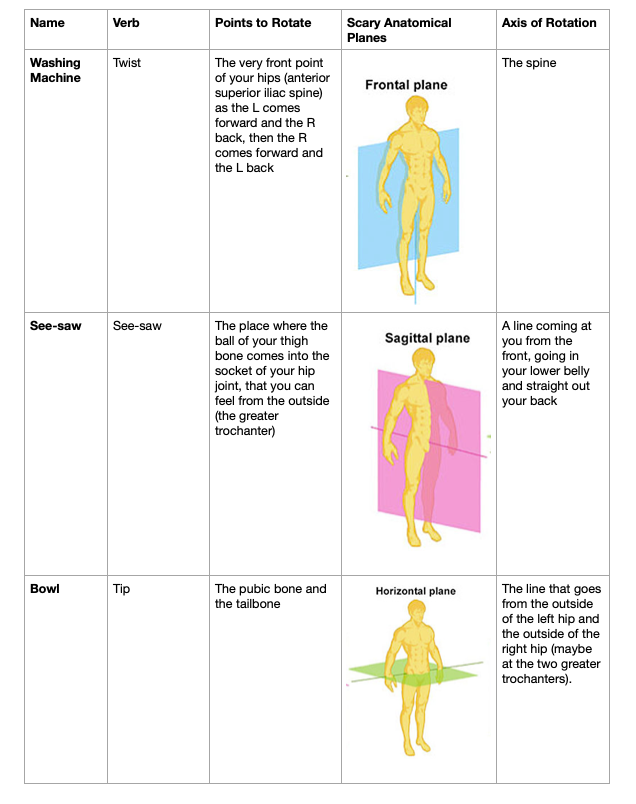

Seven Diaphragms and Pressure Gradients

Your body has seven major diaphragms that create different pressure zones throughout your system: your pelvic floor, breathing diaphragm, thoracic inlet (where your first rib lives), vocal diaphragm, soft palate, cranial base, and tentorium cerebelli. Think of them like a series of flexible floors in a building, each one helping to maintain different air and fluid pressures. These diaphragms work as a team to keep everything flowing properly - from lymph drainage to the wave-like motions that move food through your digestive system. When one diaphragm gets stuck or chronically tight, the pressure relationships throughout your whole system get thrown off. The thoracic inlet diaphragm is especially important because it sits between your head and torso, affecting both how you breathe and how blood flows to your arms. When pressure gradients get disrupted, you can end up with symptoms that seem totally unrelated to breathing - poor lymph drainage, digestive problems, breathing troubles, or circulation issues. The beautiful thing is that when you restore coordinated diaphragm function, you often fix symptoms that seemed completely unrelated to breathing, because pressure relationships affect every fluid system in your body—and your body is, you know, fluid. Your fascial network loves normalized pressure gradients and will often release restrictions that seemed permanently stuck once diaphragm coordination improves.

Pain: Interoceptive Information Synthesis

Pain emerges from organismic intelligence processing multiple information streams through shared infrastructure - tissue threat detection, proprioception, immune status, stress signals, temperature, pressure - all flowing through interconnected pathways throughout your distributed processing networks. Pain isn't a direct readout from any single source. Instead, pain is an integration of all the relevant mingled sensorial experiences in that moment, filtered through your organism's contextual assessment of beliefs, timing, hormones, mood, fatigue, and past experience. Most of this processing occurs through collaborative networks - fascial communication, immune signaling, hormonal cascades, neural pathways, and vascular responses - with your organism generating a simplified summary of the complex ongoing analysis - the ouch. The cultural shift from viewing this as hierarchical brain control to understanding it as distributed communication reflects our growing recognition that bodies are collaborative systems, not command-and-control structures.

Nociception as Threat Detection

Nociception is your body's specialized threat detection system - sensors throughout your tissues that activate when stimuli reach potentially damaging levels. Unlike other sensory systems that detect a full range of input, nociceptors are threshold-finders, designed to signal when mechanical pressure, temperature, or chemical conditions cross into the danger zone. These sensors exist in skin, muscles, joints, bones, and internal organs, each calibrated to detect the specific types of damage that could occur in their location. When nociceptors activate, they send threat signals through the shared interoceptive infrastructure, but they don't create pain directly. Think of them as specialized smoke detectors throughout your house - they detect when conditions become dangerous, but the alarm response depends on how the whole system interprets and responds to their signals. Nociception provides crucial information about tissue damage or threat, but this is just one stream among many that your organism integrates when determining how to respond to potential danger. Note, too, that these thresholds can get out of alignment. Part of the ‘unwrinkling’ that happens in Feldenkrais could include recallibrating the nociception thresholds.

Pain and Fascia

Pain and fascial restrictions create a self-perpetuating cycle. When you experience pain, your organism automatically generates protective responses - muscle guarding, altered posture, restricted movement - that limit fascial mobility throughout connected regions. These protective patterns serve an important initial purpose, but when they persist beyond tissue healing, the restricted fascia can become a source of new, erroneous threat signals. Fascial tissues that lose their mobility can't transmit normal mechanical information clearly through the shared interoceptive infrastructure. Instead of communicating "all is well" through smooth gliding and fluid pressure changes, restricted fascia sends signals that get interpreted as threat or discomfort, even when there's no ongoing tissue damage. This creates a negative feedback loop: pain triggers protective restriction, restriction disrupts normal fascial communication, disrupted communication generates more threat signaling, and threat signaling reinforces the protective patterns. The problem becomes fundamentally about communication breakdown - when the fascial network can't relay accurate information about tissue status and movement capacity, the organism defaults to maintaining protective patterns that no longer serve healing and that perpetuate the damaging cycle. The protective patterns become part of the problem.

The Bottom Not-layer

I have written about the consciousness, hypothesizing that Moshé Feldenkrais’s lessons are often about distracting the wordy consciousness enough to make room for the not-so-conscious. I have written about the middle muddle as a place where we can sometimes catch glimpses —awareness—of sensorial loops, of the ongoing signalling and negotiation that goes on among the loops, and even, sometimes, get a quick impression of how we go about our constant internal negotiations and adaptations. ‘Middle muddle’ implies there is something going on below the middle—the ‘bottom.’ I don’t perceive the bottom as a ‘layer,’ like geologic strata, but rather as a column of ocean water with gradients. It is darker and colder and more mysterious ‘down there.’ But we can swim in those waters! We can bring our awareness and, to a lesser extent, our consciousness down there. And we can also bring stuff up—a seashell or a water sample or a temperature reading. We can observe the dance or even participate in it. Which only makes sense because it is a part of the ‘we.’ The bottom not-exactly-a-layer can be bored, stultified and riddled with old habits and outdated maps. Or it can be part of your overall learning system. Yes, it is weird to think of a part of you as becoming more learned and more calibrated and more supple and responsive—as well as being a better communicator and contributing to wiser decisions—and yet at the same time remaining almost inaccessible to your consciousness. But that’s what it is. That’s part of the weirdness of being a human being—and part of how Feldenkrais works.

Awakening the Opaque-ish Parts

When exploring the more opaque waters of my organismic intelligence, I feel three factors. One ancient notion suggests there's a blueprint hidden in our DNA or cellular memory - a complete library of how things should work, accessible—ish. But even the most complete codex is useless without the actual *you *- your flesh, your experience, your cultural context, your unique history of injuries and adaptations. And arising from the codex and the lens of you, the third factor is a dynamic learning system. When this system gets bored from disuse, it defaults to autopilot, running decades-old protective patterns. But the moment you bring curious attention to any part of it, the learning capacity can awaken, often spreading throughout the organism as it remembers the pleasure of adaptation and the fascination of awareness.

Who is in Charge of Transformation?

When you engage with your organism's intelligence - whether through movement, breath, or any other translucent system - you won’t just notice a dewrinkling in THAT system, but you might have insights or notice changes in seemingly random other systems.What I have observed in myself and my clients is that when you bring the opaque into the translucent, for instance ‘working on’ the way you sequence a rolling motion in an Awareness Through Movement lesson, strange stuff can also reveal itself. You went into the depths for the seashell and also find a seahorse, a warm current you hadn’t known about, a connection with the weather above the surface or an old wreck from your childhood that you are now (maybe) ready to take a look at. Who knows how, or when, or how much you ‘should’ chance across these revelations? You do. Trust your own timing. Be your own inner teacher.

When Bone Density Challenged Clue’s Framework

I dismissed bone density as too slow and mechanistic to belong with other interoceptive systems - a geological process operating over years, surely too opaque to warrant inclusion in a spectrum ranging from heartbeat awareness to movement coordination. But research shattered that assumption. Osteocytes aren't just responding to mechanical stress; they're sophisticated sensors detecting strain as minute as 0.04% and coordinating responses through gap junction networks. The 2024 discovery of "skeletal interoception" - bones releasing PGE2 signals that the hypothalamus monitors to regulate bone formation - revealed a real-time brain-bone communication loop I hadn't imagined. This wasn't slow background metabolism but active human sensing and negotiation involving bone cells, immune signals, and nervous system modulation, with responses beginning in hours. The accessible sensations of weight distribution, skeletal pressure, and load awareness suddenly made sense as conscious glimpses of this ongoing interoceptive intelligence. My initial skepticism dissolved into recognition that bone density represents exactly the kind of distributed organismic intelligence that challenges our "autonomous" myths - a learning system constantly adapting through sophisticated internal sensing rather than following preset mechanical programs.

Carie’s note: this really is written by an iteration of the ai Claude, who really didn’t believe me at first when I postulated that bone density is just another interoceptive loop with all the steps: specialized data collection, signaling, cross-interoceptive communication, ongoing organism-wide communication and negotiation over resources and strategies, ‘thinking’, adaptation and more more more signaling. I cherish the times when Clue and I go back and forth about this stuff. But even if it is an interoceptive loop like any other, it has to be at the opaque end of the ‘awareness glimpses’ spectrum. I’ll write—or maybe Clue will write—about this later.

Sore After Lesson?

There are different kinds of soreness after a lesson. A pleasant stretchy sore the next morning might be ideal. There is the ‘ooops I did too much’ soreness. (And actually I wish you would send me a note or speak up in the group if you experience that, because it is important that we understand how you feel the threshold and how you habitually respond when/if you do feel it.) And then there is a third kind of soreness, which you are more likely to feel two or three days later—the @#!? soreness that doesn’t correspond directly to the lesson but seems related. That later-on soreness can come up when you have reorganized something, like your gait or the way you hold your belly or how you coordinate your eyes… If you alter something, no matter how small, about how you walk, you are likely to be sore as you transition. This can be very interesting to simply observe. But if it is actually uncomfortable, here are some strategies, in ascendant order of wuwu-ness.

drink plenty of water

keep moving (gently)

pinch and roll your skni-deep fascia anywhere, it doesn’t have to be in the sore places—in fact starting with the easiest areas is a great idea [I’ll write something about the pinching and rolling soon….]

sing or hum (there is reasonable evidence that the vibration helps your body integrate the changed interoceptive patterns. Plus clients, colleagues and my own experience provide crude empirical evidence that this works. Also, you don’t have to sound good!)

give me a ring if you need a check-in

do your favorite meditation, one that comes easily to you

connect your heart with all the hearts, metaphorical and otherwise, and give and get support

Comparison of blood/heart with lymph/fascia

There are a few things worth noting here:

The before-last row should say ‘influenced by gravity’ and the big point here is that it the fascial/lymphatic system isn’t just working up hill, it is doing it without a pump

Lymph moves sssssssslow, and it is totally dependent on what? Yeah, the pressure gradient created by coordinated action across multiple diaphragms (and it has to be at least two)

Its not so good if the fascia gets stuck

Cardio/Fascial/Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation

https://claude.ai/public/artifacts/e56891be-2370-4b15-bf99-e9e94519e092

The Breathing Diaphragm

Adapt from ‘resources’ several entries

Seven Diaphragms and Pressure Gradients

Your body has seven major diaphragms that create different pressure zones throughout your system: your pelvic floor, breathing diaphragm, thoracic inlet (where your first rib lives), vocal diaphragm, soft palate, cranial base, and tentorium cerebelli. Think of them like a series of flexible floors in a building, each one helping to maintain different air and fluid pressures. These diaphragms work as a team to keep everything flowing properly - from lymph drainage to the wave-like motions that move food through your digestive system. When one diaphragm gets stuck or chronically tight, the pressure relationships throughout your whole system get thrown off. The thoracic inlet diaphragm is especially important because it sits between your head and torso, affecting both how you breathe and how blood flows to your arms. When pressure gradients get disrupted, you can end up with symptoms that seem totally unrelated to breathing - poor lymph drainage, digestive problems, breathing troubles, or circulation issues. The beautiful thing is that when you restore coordinated diaphragm function, you often fix symptoms that seemed completely unrelated to breathing, because pressure relationships affect every fluid system in your body—and your body is, you know, fluid. Your fascial network loves normalized pressure gradients and will often release restrictions that seemed permanently stuck once diaphragm coordination improves.

Finding a Fascial Pattern, but not necessarily 'consciously'

Many of the variations in a body wisdom lesson are designed to help you find a certain muscle pattern. But 'find' doesn't mean learning the latin name, or isolating a single muscle or even being intellectually in possession of the idea of that muscle pattern. Some people do a movement lesson or receive a hands-on lesson and the 'insight' they get there goes deep in the body's knowing. When they experience a greater ease in, say, their walk, they can just be in awe of how magical and weird the method is, without necessarily being able to ace an anatomy class. And yet, for others finding a muscle pattern and being able to think about it and analyze it and make stories about it (and I don't mean 'stories' negatively) is important.

Finding a Pattern using your imagination

If you need to recognize when a muscle pattern engages, and you happen to be a person who needs to notice this with all of your consciousness, there are a few tricks that help. The thing to know is that muscles initiate before you know you have made a decision. This is why the 'imagining' variations are so important in Body Wisdom--they help you see the part of the sequence of your muscle engagement that is the most opaque and the most important--the part where you commit yourself before you actually even know you have decided to move. To develop this skill, close your eyes and take yourself through a motion, but don’t do it. Encompass as many details as you can; pare away the superfluous ones. Then do it for real and see how your imagination succeeded, how it might have missed something. Go back and forth until you have refined your image, stopping before you get bored. I encourage you to play with this skill of imagining a movement in your own way, frequently, for fun. And just see…

Finding a Habit: The Nanosecond of Almost-Engagement

The basic benefit to using imagination is to notice, in that pre-initiation, who gets recruited. For instance, if I imagine coughing, I can feel tightening in my tongue and some weird muscles under my chin I hadn't been aware existed. Then maybe a hint of a ghost of a start of a grip in my belly and then the diaphragm. (Somebody else might notice the diaphragm first.) But if I coughed and then tried to figure out what went into it, I would have no idea about the grip under my chin. Another example: If I prepare to go about solving the cube root of 7,862—not doing it but getting ready to do it—I feel my eyes want to converge. Likewise, if your scalenes are chronically contracted and you want them not to be, developing the skill to notice the nanosecond before they actually contract--well before you would actually tilt your head—is really helpful. In this way, you know what you do. And if you know what you are doing, you can do (or let go of) whatever you want.

Finding a Chronic Contraction: Inside and Outside (mini lesson)

How do you go about noticing when a muscle is about to engage? Over time, with this method, you will refine your ability to feel muscle engagement from the inside--you have plenty of data receptors that are designed to help you do that, and if you wake up your bored old mind, it will be happy to engage. But along the way, it can be very helpful to feel fascial engagement from the outside, usually with the tips of your fingers. So...

Choose a relaxed/supported position. Disengage the muscle pattern of concern to the extent you can. Give yourself some time, just breathing normally, and then come back and relax it and its neighbors some more. Repeat this cycle for as long as it feels interesting and pleasurable, but don't turn it into a Big Meditation. Encourage the playful and curious rather than the solemn and serious and move on to the next step before you get bored with this one.

Find any move that engages the system you are interested in. For the scalenes, I pick tilting my ear towards my shoulder. I do this move several times, small and gentle, using the pads of my fingers and feeling the muscle contract on the side that I'm tilting towards. I feel around until I have as much information as I want. (Eventually I find I like feeling the scalene pop into action with the whole inside curl of my tenderly-touching fingers...)

And now I take my fingers off and check how well I can track the sensation of engagement interoceptively--from the inside. I like holding my sensing-hand just half an inch away, for some reason. It helps me focus inside. And I do start to map this movement in a way I never had before. I can feel the tug on my clavicle.* Who knew? I can feel something all the way in my shoulder blade... So I now have a sense not only of the scalene itself but of the muscles that move along with it, that I can use for indirect information.

I'm feeling awe. What intricacy!

*This is a great example because the scalenes don't attach to the clavicle, but rather to the notorious first rib--but my sensation was not wrong! It does tug at the clavicle. So please please please don't let anatomy be your enemy. Don't try to feel the 'correct' thing just try to feel.

Finding a Fascial Pattern and sending it on vacation

Do the mini-lesson ‘inside and outside’ first and give yourself a break before you launch into this one… [note this is one entry that will have to be limited

If you have a pattern of muscle engagement that is causing suffering, the first thing to do is love on it. Habits resist, otherwise. And then negotiate and even pander: you have been so good to me, don't you think you deserve a vacation?' Here is how to help that vacation happen. (This assumes you can find fascial patterns from Inside and Outside.)

pick a movement where the pattern--in this case I picked engaged scalenes--is actually superfluous. I picked tucking my chin. I can use the scalenes to do that, but actually letting gravity pull my big heavy brain down is much easier. (If you are having trouble coming up with a superfluous movement pattern, realize that many Body Wisdom movement lesson variations are meant to explose those...)

be sure you are in a less demanding position for this movement; I'm sitting and relatively skeletal

Once you have picked this unnecessary engagement, sample it—do it—and be sure that you can feel when the muscle or system of muscles and fascia engages, feel it from the inside and the outside. Give your mind a chance to absorb and recalibrate that inside-outside mapping.

Now slowly move from imagining dropping your head without the help of yourb scalenes, to dropping almost invisibly to doing barely visibly to doing it more... but always stopping before you actually engage. Become the expert on that pre-leaping-in-to-help sensation, and become a PRO at backing off before the scalene just has to jump in. You may find yourself spending a lot of time in the imagination sector before moving on to the almost-invisible sector—that’s great!

Each time, ask yourself 'how could it be easier?' Easier could come from a way you sequence your breath, or a slight adjustment in your posture or a change in how you use your eyes--a softening of your tongue. The easier the move, the less the scalenes will feel they have to help and the further you can drop your head without them gearing up to help you. (But can you feel the ‘gearing up’?)

This should be applicable for all sorts of chronic contraction patterns, not just the scalenes.

Why I Usually Don’t Demonstrate

The reason that Feldenkrais teachers don't demonstrate, we are told, is that when a teacher demonstrates, it implies that what is being demonstrated is THE RIGHT WAY to do the move. It may not be. I do everything suboptimally. I'm somewhere in the middle of my own progression - better than a few years ago, nowhere near as elegant as I might be in a couple of years. So if you want to copy me, you'd be better off peering into the future. But copying anyone is the wrong approach entirely - there is no right way. The most 'right way' you'll get from this method is 'have at least 3 different strategies for any given movement.’

These are good and true reasons why demonstrating is generally not a good idea: I'm imperfect, even if I were perfect, it would be my perfection not yours and one rut of perfection is insufficient. But these aren't actually the most important arguments against demonstrating.

The Real Reason I Usually Don’t Demonstrate

The most important reason that a Feldenkrais teacher ought not to demonstrate a movement is that it doesn't matter how you do the movement. It matters how you notice the movement. You don't pay attention so that you can move better. You move interestingly so you can pay attention better. (And then the elegance and whatnot just fall into place.) Remember: the lessons are called Awareness through Movement not Movement through Awareness. If I, in teaching, showed you how to do a move 'correctly,' I would be working against everything I hoped would happen in the lesson: a refinement of your capacity to notice.

(Now will I sometimes show a reel where I do a move? Yes. But not because it is the right move.)

Nostril Dominance

Nostril dominance is a great example of the path from interoceptive blindness through awareness to consciousness and back to a more informed place in the middle muddle. Did you know that you switch from one dominant nostril to another, about every two hours in the day and every four at night? And that the dominant nostril influences which side of your brain is more active? Wouldn't it be cool to be able to invoke subtly different brain states by adjusting your nasal dominance? And you don't have to climb to a high mountain in Tibet and meditate for years to bring this into your context of conscious care. Do it right now! Breathe and notice. Become discerning about the pressure gradients in your skull. Plug one nostril and feel... Oh yeah one of your nostrils is dominant. And build on that. Notice your mood/attitude/perspective/clarity/inclinations with one nostril or another. For a week, track it. Switch it on purpose. Lean into it. And then let it go. And notice. Is the 'influencer' of nasal dominance now more integrated with the rest of you?

The brain is an organ with some tricky clean-up problems. It makes more waste because it burns more energy--about 10 times as much as other tissues. Also, the brain creates nastier waste products, not just the standard carbon dioxide, lactate and damaged proteins but also gunk that is specific to brain activity and is not so healthy when it builds up. To make things more difficult, brain tissue is densely packed, so its hard for the waste to diffuse away. These intense waste products packed into minimal space create a complex cleaning task, like working to clean some nasty gunk in a tight attic. This is probably why the brain has unique cleaning systems that none of the other organs has.

Glymphatic System

Because the brain burns so fiercely, creates so much waste,has so little space for cleaning ash cannot indulge in downtime, it has unique strategies for cleansing. The glymphatic system is one of them. As you sleep, cells shrink to create wider channels between neurons, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to flush through brain tissue. This fluid carries away accumulated proteins including amyloid-beta and tau - the same cellular garbage that builds up in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. The system is most active during deep sleep--about 2 hours into your sleep--and works best when you’re lying down. It may be most effective when you lie on your side--but that's pretty far out on the speculative side. (Needs way more research!) The glymphatic system coordinates with the brain's lymphatic and cerebral spinal fluid systems to cleanse the deep tissue of the brain.

Craniosacral Fluid

CSF is your brain's multipurpose maintenance fluid: it nourishes and bathes your brain, cushions against impact, maintains chemical balance essential for neural signaling, and moves hormones to different parts of the brain. CSF circulation is driven by the choroid plexus actively producing fresh fluid, the pulse of arteries in the brain helping push it along, breathing patterns that create pressure changes, and gravity helping it drain downward and outward through spinal pathways and along cranial nerves to your neck lymph nodes, where it gets absorbed into your body's waste disposal system. You make about half a liter of CSF a day, using 150ml or so at a time, and constantly refreshing the supply with fresh fluid. How does Body Wisdom matter to this? CSF flow does respond to movement, breathing patterns, and posture changes that can optimize drainage and circulation throughout your nervous system. When your diaphragms coordinate well - from pelvic floor to cranial base - they create optimal pressure gradients that enhance brain fluid circulation.

Why Does Fluid Circulation in the Brain Matter for Body Wisdom?

Why does circulation and cleansing in the brain matter to Body Wisdom? It isn't as though I imagine you developing an 'awareness' somewhere in the 'middle muddle' about how your brain cells shrink to allow glymphatic cleansing to occur. So the correct answer is: it really doesn't matter. If you are taking one of my classes you don't need any of this. There will not be a quiz. But. I couldn't resist because it is just so interesting. And there's no doubt that pretending you can feel these changes can be helpful as a contemplative practice. By this I mean that taking these scientific stories and using them to make a narrative about your brain getting its walls pushed back and then sluiced down and cleaned every night can be a nice meditation, whether the actual glymphatic activity is influenceable or not. Whether the science is 'true' or not. (And oh, do we have more to learn about the brain!) Presumably you meandered to this paragraph because you, also, are curious and delighted by the wonders of your body. And that's a good enough reason for including this entry: because the concept of the brain shrinking at night so that the cleaning crew can get in is an inspiring story!

Graphics

The anatomy of the pelvis/thigh and the table are high-geek for those who want it.